A CONTRIBUTION FROM THE RQOH TO THE WORK OF THE HUMA COMMITTEE │ FEBRUARY 2017 RQOH.COM

Fighting poverty is at the heart of the community housing’s mission. While the Canadian government is considering the strategies it should implement to attain this objective, it should be clear that access to safe, adequate and affordable housing is a central pillar of any strategy aiming at reducing poverty.

Housing and the fight against poverty

right_to_housing_fight_against_poverty_feb_2017_web

Download PDF file

Initiatives designed to promote housing affordability and put an end to homelessness are central to the efforts we must make to reduce poverty. Much work remains to be done for the right to housing to become a universal reality, and RQOH has great hopes for the new National Housing Strategy the Government of Canada will soon be announcing, the purpose of which is to ensure that all Canadians have the “right to safe, adequate, and affordable housing.”

Since housing is an essential need, its cost and the percentage of household income it represents are among the main determinants of poverty. Conversely, access to affordable housing increases households’ ability to escape poverty and improve their condition in a sustainable way. It is outrageous that, despite past efforts, more than 1.6 million tenant households must spend more than 30% of their incomes on rent, and nearly 800,000 of them more than half.[1]

Most households finding themselves in these situations of housing insecurity come from groups that are subject to discriminatory practices: indigenous people, single-parent families, low-income individuals, racialized groups, persons with physical disabilities or mental health disorders, and so on. It would be wise to view the problems of access to suitable housing—and strategies to address them—from a human rights’ standpoint.

The international community has long recognized the universal nature of the right to housing, which is viewed as an integral part of the “right to an adequate standard of living” provided for in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights and expressly stated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Canada ratified in 1976. As others have done, we propose:

That the right to safe, adequate, and affordable housing be expressly recognized in Canada’s legal human rights instruments.

Although there is an obvious correlation between the cost of housing and disposable income, the extent of the impact of housing affordability on the living conditions of households in difficulty is not always accurately measured.

1,662,885 Vulnerable Household Tenants in Canada

Studies show that, when housing expenses represent too large a percentage of income, spending on other essential needs suffers, starting with food.[2] Vulnerable persons are then caught in a spiral of poverty, in which housing insecurity triggers or exacerbates food insecurity, social disaffiliation, and mental disorders, of which homelessness is an extreme form. For these reasons, we propose:

Studies show that, when housing expenses represent too large a percentage of income, spending on other essential needs suffers, starting with food.[2] Vulnerable persons are then caught in a spiral of poverty, in which housing insecurity triggers or exacerbates food insecurity, social disaffiliation, and mental disorders, of which homelessness is an extreme form. For these reasons, we propose:

That poverty reduction strategies call for targeted efforts combined with specific objectives to address housing affordability problems.

By affordability, we mean, first, housing at a cost consistent with the financial capacity of households, but that also includes housing that suits their particular needs (type, adaptability, location, etc.). In our view, community housing is the best option for ensuring housing affordability.

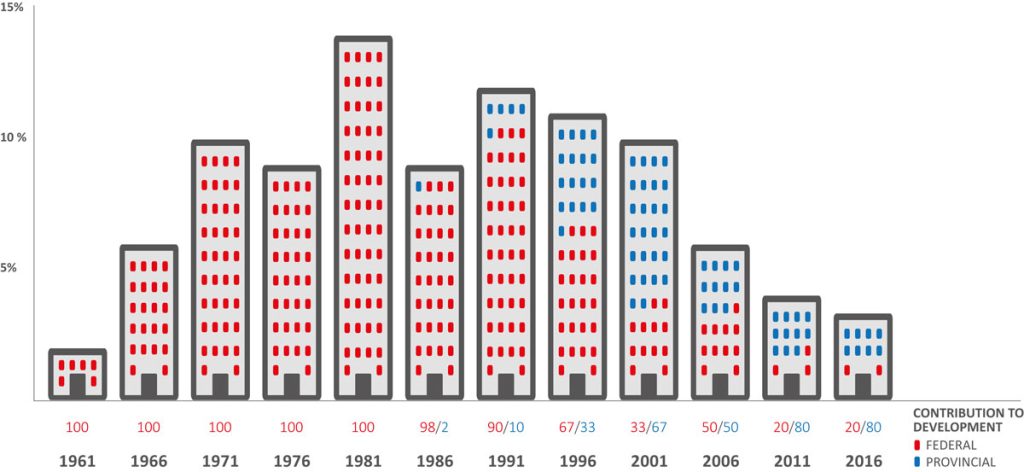

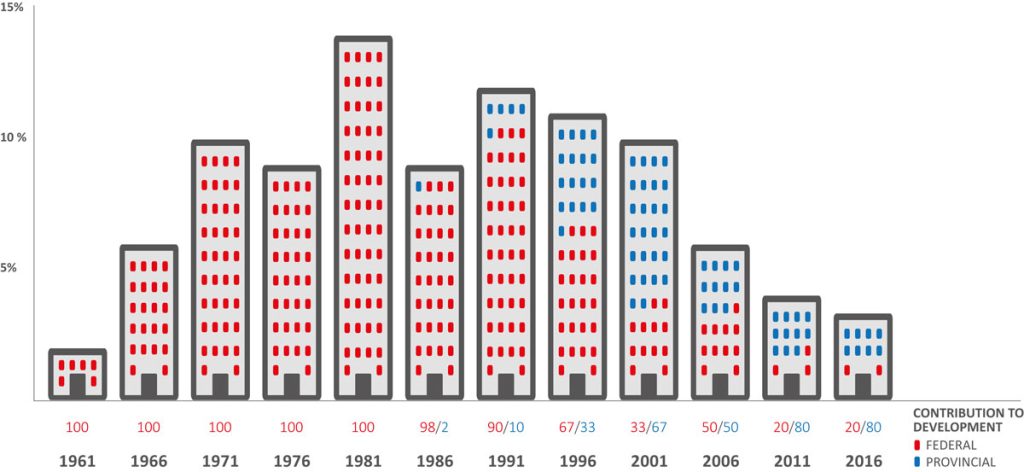

Housing action by the Government of Canada used to promote affordability, helping hundreds of thousands of households hold their heads high and find conditions conducive to their participation in society. It also helped enrich communities. However, the change in direction toward private-sector assistance put a stop to that development, and, in the past 20 years, the share of social housing as a percentage of Canada’s total housing stock has fallen from nearly 9% to only 3.7%. At the same time, the overheating of the housing market led to an increase in the housing costs for renter households much higher than that of their incomes.

Following the consultations that CMHC conducted last fall in anticipation of the new National Housing Strategy, Minister Duclos said he thought the strategy should be a vehicle for social inclusion and should help Canadians “who face housing barriers every day, including individuals and families at risk of or experiencing homelessness.”[3]

The National Housing Strategy should include among its aims the reduction of poverty; its impact should then be measured based on that objective.

Share of Social and Community Housing in

Canada’s Residential Housing Stock

Community housing as a strategy

Community housing as a strategy

The advantage of community housing is that it is a lasting solution to housing affordability problems, is adaptable to the diverse range of clienteles, and is rooted in the needs of the communities. The non-profit housing stock is not subject to speculation, and rents, which are initially low, rise more slowly than in the private market.

The data gathered from organizations that administer the federal stock reveal a gap of nearly 33% between the median rent of non-profit housing units and that of the market. The average rent supplements offered ($230 in 2013) appear to be lower than those granted in the private market ($316), which are not perennials.[4]

As regards the fight against poverty, a study conducted for the Société d’habitation du Québec[5] identified five major impacts of social and community housing: an increase in disposable income to purchase essential goods; the creation of a living environment conducive to social and professional integration; greater academic success; a reduction of socioeconomic inequalities and a deconcentration of poverty; and, lastly, a decline in the use of public services.

Furthermore, based on a comparison of the employment incomes of households living in social housing with those of households awaiting such housing, the authors noted that access to affordable housing may promote efforts to take training and find employment. Households that have occupied their housing units for longer periods of time also represent a larger percentage of beneficiary households for which employment income is their principal income. Social housing would thus appear to be part of a dynamic of emerging from poverty.

As part of CMHC’s consultations, RQOH suggested three themes around which the future National Housing Strategy should be developed:

- Protection of the existing social and community housing stock;

- A development plan for at least 600,000 new non-profit housing units by 2035;

- The implementation of mechanisms for the financial, legal, and organizational sustainability of non-profit housing.[6]

We suggest:

That these three objectives be incorporated into the Canadian poverty reduction strategy.

However, although strictly financial unaffordability is an essential issue, it is not the only factor contributing to the housing problems that many households encounter. People living in poverty often face related problems that push them toward social disaffiliation, and organizations that combine housing and community services appear to be particularly well suited to addressing them.

Québec’s non-profit housing organizations have developed a method for intervening with clienteles living in their properties that promotes residential stability, social integration, and citizen participation. Supported by the health and social services network, community social housing support includes actions ranging from reception to referral and embracing assistance, conflict management, and crisis intervention (see example in sidebar).

These actions are designed to promote personal self-sufficiency. They help identify situations in which a person may find it difficult to avoid reverting to a housing insecurity dynamic. These actions have proven to be particularly effective with clienteles that have emerged from or are at risk of homelessness.

As a result of its collective nature, community housing thus becomes an anchor point that facilitates the pooling of public and community resources available for households in difficulty. From being a determinant of poverty, housing thus becomes the starting point of a path to better living conditions. For this reason, we recommend:

That the Government of Canada’s future housing actions and programs promote the development of non-profit housing with community support in partnership with the social services and community networks.

Banking on community mobilization

The social housing projects whose impact has proven to be the most profound and lasting are those that have been developed and implemented through community mobilization. In this way, communities ensure that those projects meet real needs and that the community at large will take part in their implementation and long-term operation.

This mobilization and engagement are apparent in the vitality of the non-profit housing organizations, as may be seen from the variety of projects those organizations have completed and the participation of the thousands of volunteers and salaried employees who work there every day (see example in sidebar).

As the Government of Canada prepares to adopt its National Housing Strategy, the community wants and awaits an orientation and a form of intervention consistent with the right to housing, one that is replete with ambitious objectives. The resulting programs must support the implementation of new community housing projects and the households that will benefit from them. These programs will be all the more efficient if designed to facilitate the mobilization and pooling of the resources of the organizations and the community.

This is the gist of the proposals we have made and that we submitted to Minister Duclos and to CMHC over the past year to support the development and continuation of community housing projects. In that same spirit, we propose:

That the Canadian poverty reduction strategy promotes coordination of the actions of the organizations and partners involved in the communities; in the area of housing, that should result, in particular, in programs that facilitate the mobilization and pooling of available resources and support the actions of community housing organizations.

EXAMPLE

Centre inter-section

Located in Gatineau, Centre Inter-section offers 35 housing units for people with mental health problems. Community support is at the heart of its mission and includes: intervention and social reintegration services, recreation, education, psychosocial support, employability programs and support to persons in grief after the suicide of a relative or friend.

EXAMPLE

L’Avenue

L’Avenue’s mission is to promote social and economic integration of homeless people and those at risk, particularly men and women between 18 and 30 years of age. Through short- and medium-term housing, supportive housing and social housing, L’Avenue aims to help young people get off the streets and integrate in society in a flexible and sustainable way. Beyond a roof and concrete help, L’Avenue is a space where young adults can come to improve their conditions, to anchor in a living environment and to break their isolation. Their stay could not be a success without the backing of an intervention team that supports them on a daily basis.

[1] Canadian Rental Housing Index, http://rentalhousingindex.ca

[2] AECOM Aménagement, Environnement et Ressources, 2013, Étude sur les impacts sociaux des activités de la Société d’habitation du Québec, http://www.habitation.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/internet/publications/0000022972.pdf

[3] Conference Board of Canada, 2016, What we heard: Shaping Canada s National Housing Strategy, https://www.letstalkhousing.ca/pdfs/what-we-heard.pdf

[4] Aubin, Jacinthe, 2013, Rapport d’évaluation du Programme de supplément au loyer, Société d’habitation du

Québec, http://www.habitation.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/internet/publications/0000022518.pdf

[5] AECOM Aménagement, Environnement et Ressources, 2011, Étude d’impacts des activités de la Société d’habitation du Québec, http://www.habitation.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/internet/publications/0000021371.pdf

[6] RQOH, 2016, Parce qu’un logement c’est un droit, https://rqoh.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Memoire_RQOH_SCHL_parlons_logement_vf.pdf

Studies show that, when housing expenses represent too large a percentage of income, spending on other essential needs suffers, starting with food.

Studies show that, when housing expenses represent too large a percentage of income, spending on other essential needs suffers, starting with food. Community housing as a strategy

Community housing as a strategy